So you want a cheap ML workstation

Updated 2025-05-27 / Created 2024-02-25 / 3.61k words

How to run local AI slightly more cheaply than with a prebuilt system. Somewhat opinionated.Summary

- Most of your workstation should be like a normal gaming desktop, but with less emphasis on single-threaded performance and more RAM. These are not hard to build yourself.

- Buy recent (3000-series and onward) consumer Nvidia GPUs with lots of VRAM (not datacentre or workstation ones).

- Older or used parts are good to cut costs (not overly old GPUs).

- Buy a sufficiently capable PSU.

- For specifically big LLM inference, you probably want a server CPU (not a GPU) with lots of memory and memory bandwidth. See this section.

Programmers love talking about the “bare metal”, when in fact the logic board is composed primarily of plastics and silicon oxides.

Long version

Thanks to the osmarks.net crawlers scouring the web for bloggable information[1], I've found out that many people are interested in having local hardware to run machine learning workloads (by which I refer to GPU-accelerated inference or training of large neural nets: anything else is not real), but are doing it wrong, or not at all. There are superficially good part choices which are, in actuality, extremely bad for almost anything, and shiny prebuilt options which are far more expensive than necessary. In this article, I will outline what to do to get a useful system at somewhat less expense[2].

Do not fear hardware (much)

If you mostly touch software, you might be worried about interacting with the physical world, such as by buying and assembling computer hardware. Don't be. Desktop computer hardware is heavily standardized, and assembly of a computer from parts can easily be done in a few hours by anyone with functional fine motor control and a screwdriver (there are many free high-quality guides available). As long as you're not doing anything exotic, part selections can be automatically checked for compatibility by PCPartPicker, and many online communities offer free human review. Part selection is also not extremely complicated in the average case, though some knowledge of your workload and basic computer architecture is necessary. I am not, however, going to provide part lists, because these vary with your requirements and with local pricing. You may want to ask r/buildapc or similar communities to review your part list.

GPU choice

The most important decision you will make in your build is your choice of GPU(s) – the GPU will be doing most of your compute, and generally define how capable the rest of your components need to be. You can, practically, run at most two on consumer hardware (see Scaling up for more).

Submit to Jensen

Unless you want to spend lots of your time messing around with drivers, Nvidia is your only practical choice for compute workloads. Optimized kernels[3] such as Flash Attention are generally only written for CUDA, hampering effective compute performance on alternatives. AMD make capable GPUs for gaming which go underappreciated by many buyers, and Intel... make GPUs... but AMD does not appear to be taking their compute stack seriously on consumer hardware[4] and Intel's is merely okay[5].

AMD's CUDA competitor, ROCm, appears to only be officially supported on the highest-end cards, and (at least according to geohot as of a few months ago) does not work very reliably even on those. AMD also lacks capable matrix multiplication acceleration, meaning its GPUs' AI compute performance is lacking – even the latest RDNA 3 hardware only has WMMA, which reuses existing hardware slightly more efficiently, resulting in the top-end RX 7900 XTX being slower than Nvidia's last-generation RTX 3090 in theoretical matrix performance. The AMD RX 9070 XT now has competent matrix acceleration, but the RDNA 4 generation doesn't have anything higher-end than it, and it only has 16GB of VRAM and mediocre bandwidth.

Tenstorrent Blackhole is a very credible competitor – hardware-wise. The compute is on par with an RTX 4090, and they are cheaper and have more VRAM, although less VRAM bandwidth. The p150a has absurdly fast networking for scale-out (multi-accelerator) workloads. However, the software is barely functional – they have gone through several software stacks, basic features are broken and, at least based on the open bounties and discussion on the Discord, they appear more concerned with making specific workloads run than a general solution (making their compiler robust). Additionally, idle power consumption is ~100W with the current firmware, as opposed to ~10W for a modern GPU, which adds lots to effective cost, and as they aren't GPUs they can't do display output themselves.

Intel GPUs have good matrix multiplication accelerators, but their most powerful (consumer) GPU product is not very performant and the software is problematic – Triton and PyTorch are supported, but not all tools will support Intel's integration code, and there is presently an issue with addressing more than 4GB of memory in one allocation due to their iGPU heritage which apparently causes many problems.

Do not buy datacentre cards

Many unwary buyers have fallen for the siren song of increasingly cheap used Nvidia Tesla GPUs, since they offer very large VRAM pools at very low cost. However, these are a bad choice unless you only need that VRAM. The popular Tesla K80 is 9 years old, with lacking driver support, no FP16, extremely lacking general performance, high power consumption, and no modern optimization efforts, and it's not actually one GPU – it's two on a single card, so you have to deal with parallelizing anything big across GPUs. The next-generation Tesla M40 has similar problems, although it is a single GPU rather than two, and the P40 is not much different, though instead of no FP16 it has unusably slow FP16[6]. Even a Tesla P100 is lacking in compute performance compared to newer generations. Datacentre cards newer than that are not available cheaply. There's also some complexity with cooling, since they're designed for server airflow with separate fans, unlike a consumer GPU.[7]

It may look innocent, but it is a menace to unaware hobbyists.

Do not buy workstation cards

Nvidia has a range of workstation graphics cards. However, they are generally worse than their consumer GPU counterparts in every way except for VRAM capacity, sometimes compactness, and artificial feature gating (PCIe P2P and ECC): the prices are drastically higher (the confusingly named RTX 6000 Ada Generation ("6000A") sells for about four times the price of the similar RTX 4090), the memory bandwidth lower (consumer cards use GDDR6X, which generally offers higher bandwidth, but workstation hardware uses plain GDDR6 due to power) and performance in practice worse even when on paper it should be better. The 6000A has an underpowered cooler and aggressively throttles back under high-power loads, resulting in drastically lower performance.[8]

Workload characteristics

As you can probably now infer, I recommend using recent consumer hardware, which offers better performance/$. Exactly which consumer hardware to buy depends on intended workload. There are typically only three relevant metrics (which should be easy to find in spec sheets):

- Memory bandwidth.

- Compute performance (FP16 tensor TFLOP/s).

- VRAM capacity.

VRAM capacity doesn't affect performance until it runs out, at which point you will incur heavy penalties from swapping and/or moving part of your workload to the CPU. Memory bandwidth is generally limiting with large models and small batch sizes (e.g. online LLM inference for chatbots[9]), and compute the bottleneck for training and some inference (e.g. Stable Diffusion and some other vision models)[10]. Within a GPU generation, these generally scale together, but between generations bandwidth usually grows slower than compute. Between Ampere (RTX 3XXX) and Ada Lovelace (RTX 4XXX) it has in some cases gone down[11].

As VRAM effectively upper-bounds practical workloads, it's best to get the cards Nvidia generously deigns to give outsized amounts of VRAM for their compute performance, unless you're sure of what you want to run. This usually means a RTX 3060 (12GB), RTX 3090 or RTX 4090. RTX 3090s are readily available used far below the official retail prices, and are a good choice if you're mostly concerned with inference, since their memory bandwidth is almost the same as a 4090's, but 4090s have over twice as much compute on paper and (in non-memory-bound scenarios) also bear this out in practice. RTX 5090s are a significant upgrade, but cost over twice as much.

Native BF16 support is important too, but Ampere and Ada Lovelace both have this. It looks like RDNA3 (AMD) does, even.

Multi-GPU

You can run two graphics cards in a consumer system without any particularly special requirements – just make sure your power supply can handle it and that you get a mainboard with PCIe slots with enough spacing between them. Each GPU will run with 8 PCIe lanes, via PCIe bifurcation. Any parallelizable workload which fits onto a single card should work at almost double speed with data parallelism, and larger models can be loaded across both via pipeline or tensor parallelism. Note that the latter requires fast interconnect between the GPUs. To spite users[12], only the RTX 3090 has NVLink, which provides about 50GB/s (each direction) between GPUs[13], and only workstation GPUs have PCIe P2P enabled[14], which reduces latency and increases bandwidth when using standard PCIe between two GPUs. However, you can get away without either of these if you don't need more than about 12GB/s (each direction) between GPUs, which I am told you usually don't.

Technically, you can plug in more GPUs than this (up to 4), but they'll have less bandwidth and messing around with riser cables is usually necessary.

Power consumption

GPUs are pretty power-hungry. PCPartPicker will make a good estimate of maximum power draw in most cases, but Ampere GPUs can briefly have power spikes to far above their rated TDP[15]. A good PSU may handle these without tripping overcurrent/overpower protection, but it's safer to just assume that a RTX 3090 has a maximum power draw of 600W and choose a power supply accordingly.

If you're concerned about reducing your power bill, Ada Lovelace GPUs are generally much more efficient than Ampere due to their newer manufacturing process. You can also power-limit your GPU using nvidia-smi -pl [power limit in watts] (note that this must be run each boot in some way): this does reduce performance, but nonlinearly.

Thanks to "snowy χατγιρλ/acc" on #off-topic for the benchmark. Other GPUs will have different behaviour. This is something of a worst case though – you'll lose less to power limits in real workloads.

Other components

Obviously computers contain parts other than the GPU. For the purposes of a pure ML workstation, these don't really matter, as they won't usually be bottlenecks (if you intend to debase your nice GPU by also running games and other graphical tasks on it, then you will of course need more powerful ones). Any recent consumer CPU should be more than capable of driving a GPU for running models. For more intensive work involving heavy data preprocessors or compilation you should prioritize core count over single-threaded performance (e.g. by buying a slightly older-generation higher-core-count CPU). Every good-quality NVMe SSD is fast enough for almost anything you might want to do with it. Your build will not be very different from a standard gaming computer apart from these minor details, so it's easiest to take a good build for one of those and make the necessary tweaks.

One thing to be concerned about, however, is RAM. If you do anything novel, most of the code you will run will be "research-grade" and consume far more RAM than it should. To work around this, you should make sure to buy plenty of RAM (at the very least, more CPU RAM than VRAM) or to use a very big swap file, as this is much more practical than fixing all the code. If possible, buy the biggest single DIMMs (memory modules) you can, as running more or fewer than two sticks will cut your CPU's memory bandwidth – while not performance-critical like GPU memory bandwidth, there's no reason to incur this hit unnecessarily.

Also note that modern GPUs are very big. You should be sure that your case supports the length and width of your GPU, as well as the height of your GPU plus its power cables.

Addenda

CPU inference

While I don't like this myself, you might be interested in slowly running very large language models interactively and nothing else. This is when datacentre GPUs might, for once, be sane (still not K80s), as well as running on CPU. To a first approximation, one token generated requires two FLOPS (one fused multiply-add) per parameter regardless of quantization, and loading every weight into cache from RAM once. Here is (roughly) the compute and memory bandwidth available with various hardware:

| Hardware | TFLOP/s | Bandwidth (GB/s) | Ratio (FLOPS/B) | Capacity (GB) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090 | 165 | 1008 | 163 | 24 | FP16 dense tensor TFLOP/s from spec sheet (FP32 accumulate). |

| Nvidia GeForce RTX 3090 | 71 | 936 | 75 | 24 | As above. |

| Nvidia GeForce RTX 3060 (12GB) | 25 | 360 | 70 | 12 | As above. |

| Nvidia Tesla K80 (one GPU) | 4 | 240 | 16 | 12 | Each Tesla K80 card contains two individual GPU chips. They do not have FP16, so I'm using FP32 numbers. |

| Nvidia Tesla M40 | 7 | 288 | 24 | 24 | Still no FP16, but only one GPU per card. It has less aggregate bandwidth than a whole K80 card as a result. |

| Nvidia Tesla P40 | 12 | 347 | 34 | 24 | It has hardware FP16 but crippled, so I use FP32 figures. |

| AMD Ryzen 9 7950X | 2.5 | 83 | 30 | <=192 | TFLOP/s estimated from AVX-512 figures here. Bandwidth is theoretical, assuming DDR5-5200 dual-channel (I think in practice Infinity Fabric links bottleneck this). Using four DIMMs will reduce rated RAM speed a lot. |

| AMD Ryzen 7 7800X | 1.3 | 83 | 16 | <=192 | Basically half a 7950X in terms of compute. |

| Intel Core i9-14900K | 2.5 | 90 | 27 | <=192 | No AVX-512, but the same amount of floating point execution capacity as AMD on P-cores, I think. Each E-core (Gracemont) provides half as much per cycle. I am assuming maximum turbo frequencies on all cores at once. Rated memory bandwidth is slightly higher than AMD's (on DDR5). |

| Intel Core i9-14600K | 1.5 | 90 | 16 | <=192 | As above. |

| Intel Xeon Platinum 8280 | 4.8 | 141 | 34 | <=1024 | Just for fun (these, and boards for them, are hard to get, though easier/cheaper than modern server CPUs). Compute is overestimated as these downclock badly in heavy AVX-512 loads. |

| Apple M1 Ultra | 21 | 819 | 27 | 128 | Apple Silicon has a bizarrely good memory subsystem. I'm counting its GPU TFLOP/s here. |

One forward pass of an LLM with FP16 weights conveniently also requires loading two bytes per weight, so the FLOPS per byte ratio above is (approximately; I'm rounding off many, many details here) how many tokens can be processed in parallel without slowdown. Since sampling (generating outputs) is inherently serial you don't benefit from possible parallelism (except when processing the prompt), so quantization (which reduces memory bandwidth and slightly increases compute costs) has lots of room to work. In principle the FLOP/byte ratio should be high enough with everything that performance is directly proportional to bandwidth. This does not appear to be true with older GPUs according to user reports, probably due to overheads I ignored – notably, nobody reports more than about 15 tokens/second. Thus, despite somewhat better software support, CPU inference is usually going to be slower than old-datacentre-GPU inference, but is at least the best way to get lots of memory capacity.

MoE models

I have seen a noticeable uptick in search traffic to this page recently, which I assume is because of interest in DeepSeek-R1 and running it locally. If you're not aware, people often use "R1" to refer to either the original 671-billion-parameter DeepSeek-V3-based model or the much smaller (<70B) finetunes of other open-source models. These are different in many ways – the former is much smarter but hard to run.

Mixture of Experts models are a way to improve on the compute-efficiency of standard "dense" transformers by using only a subset of parameters in each forward pass of the model. This is good for large-scale deployments, where one instance of a model is deployed across tens or hundreds of GPUs, because of lower per-token compute costs, but unfortunately quite bad for local users, because you need more total parameters for equivalent performance to a dense model and thus more VRAM capacity for inference.

Most open-source language models (LLaMA, etc) are either small enough to fit on one or two GPUs, or compute-intensive enough (LLaMA-3.1-405B, for instance) that home users could only feasibly fit them on CPU RAM but would then experience awful (~1 token per second) speeds. DeepSeek-V3 (and thus -R1), however, is an MoE model – only 37B of the 671B total parameters are needed for each token, so bandwidth requirements are much lower, so with enough RAM capacity it can theoretically run at slow-GPU-system speeds of ~10 tokens per second. You'll need a server platform to fit this much RAM, and RAM itself is quite expensive, though. See this article on a $2000 single-socket AMD EPYC build doing ~4 tokens per second on the quantized model. See this Twitter thread for a $6000 dual-socket build doing ~8 tokens per second on the unquantized model. This is significantly below the theoretical limit (~25 t/s) so better software should be able to bring it up. I don't think it's possible to do significantly better than that without much more expensive hardware.

Scaling up

It's possible to have more GPUs without going straight to an expensive "real" GPU server or large workstation and the concomitant costs, but this is very much off the beaten path. Standard consumer platforms do not have enough PCIe lanes for more than two (reasonably) or four (unreasonably), so HEDT or server hardware is necessary. HEDT is mostly dead and new server hardware increasingly expensive and divergent from desktop platforms, so it's most feasible to buy older server hardware, for which automated compatibility checkers and convenient part choice lists aren't available. The first well-documented build I saw was this one, which uses 7 GPUs and an AMD EPYC Rome platform (~2019) in an open-frame case designed for miners, although I think Tinyboxes are intended to be similar. Recently, this was published, which is roughly the same except for using 4090s and a newer server platform. They propose using server power supplies (but didn't do it themselves), which is a smart idea – I had not considered the fact that you could get adapter boards for their edge connectors. Also see this, which recommends using significantly older server hardware – I don't really agree with this due to physical fit/power supply compatibility challenges.

They describe somewhat horrifying electrical engineering problems due to using several power supplies together, and custom cooling modifications. While doable, all this requires much more expertise than just assembling a standard desktop from a normal part list. Your other option is to take an entire old server and install GPUs in it, but most are not designed for consumer GPUs and will not easily fit or power them. I've also been told that some of them have inflexible firmware and might have issues running unexpected PCIe cards or different fan configurations.

Not really. ↩︎

High-performance compute hardware is still not cheap in an absolute sense, and for infrequent loads you are likely better off with cloud services. ↩︎

Meaning optimized code for a specific computing task, not OS kernels. ↩︎

I'm told it works

fineslightly better on their latest datacentre cards. You are not getting those. You aren't even renting those, for some reason. ↩︎Intel's is arguably better on consumer hardware than datacentre, as their datacentre hardware doesn't work. ↩︎

You should be able to hold weights in FP16 and do the maths in FP32, giving you FP32 speeds instead of the horrible slowdown, though. ↩︎

This is not hard to fix with aftermarket fans and a 3D printer and/or zip ties. ↩︎

I don't seem to have a source for this (probably old Discord conversations), but I'm obviously right. ↩︎

Especially since most LLM quantization dequantizes to FP16 before doing the matrix multiplications, sparing no compute but lots of bandwidth and VRAM. ↩︎

Tim Dettmers has a good technical explanation of this, though many of the specific recommendations it makes are outdated, Nvidia is now known to artificially limit FP16 tensor performance with FP32 reduction on both Ada Lovelace and Ampere, and the structured sparsity feature has not had any real adoption. ↩︎

Compare the RTX 3060 and RTX 4060, for instance. It's still faster for gaming because of caches compensating for this and higher clocks providing more compute. ↩︎

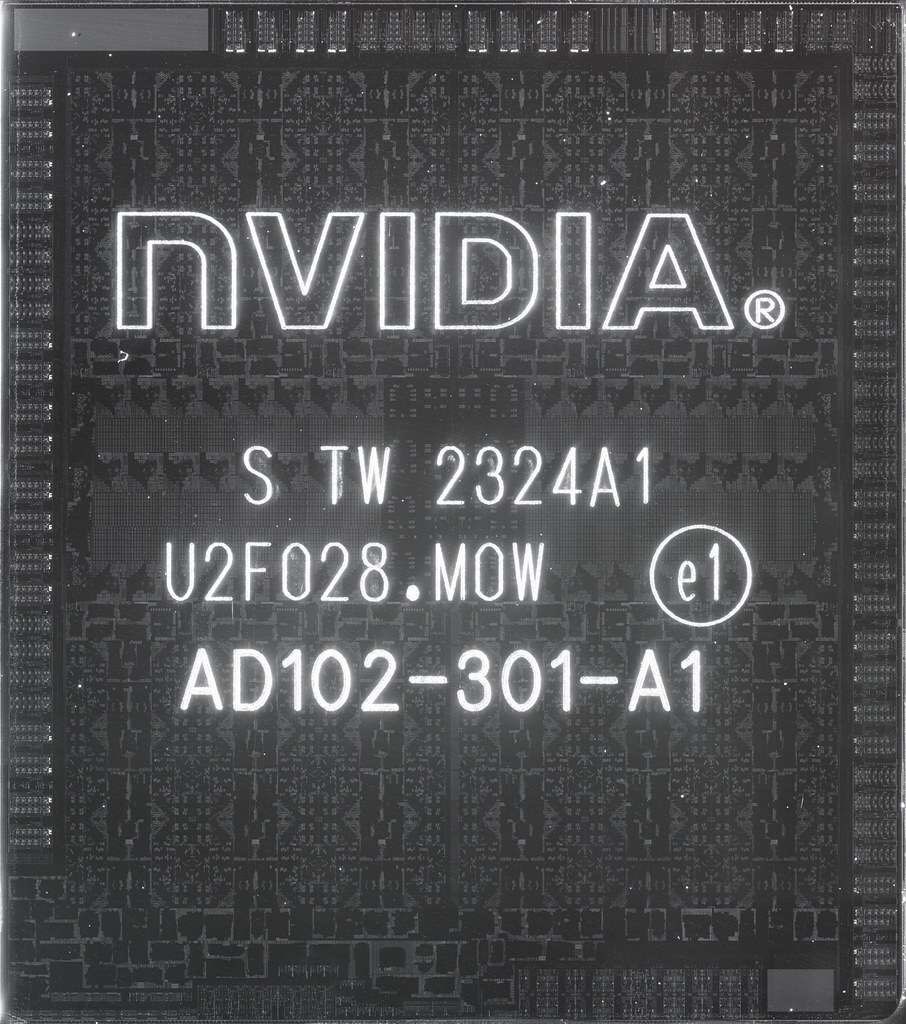

The AD102 chip in the RTX 4090 even appears to have had NVLink removed late in development (see the blank areas around the perimeter):

(image source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/130561288@N04/53156939446/). ↩︎

(image source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/130561288@N04/53156939446/). ↩︎I don't know the theoretical link rate, but it's benchmarked here. ↩︎

Geohotz/Tinygrad now has a patch to the open-source kernel module which makes it work, at least on 3090s and 4090s, by hacking it into using native PCIe capabilities which are retained. ↩︎